The People of San Pablo Avenue and the Dignity of PLace-Making by Audrey McClish

From the grandeur high-rises of downtown Oakland to the seaside wetlands of Hercules and Rodeo, our journey along San Pablo this semester represented a lot of the themes that I have learned about in the classroom. Drawing on political economy, we talk a lot about how people shape the spaces we inhabit- through movements of capital, gentrification, industry and transportation, methods of racialization, accumulation, and inequality. These themes were all very apparent in the shifting scenes between enormous high-rises, to unhoused communities in the underpass, strip malls and shopping complexes, to old abandoned industrial wharehouses, discarded lots, to community gardens and boutique downtowns. I felt myself most drawn to how people were making lives and communities in distinct ways within the changing landscape.

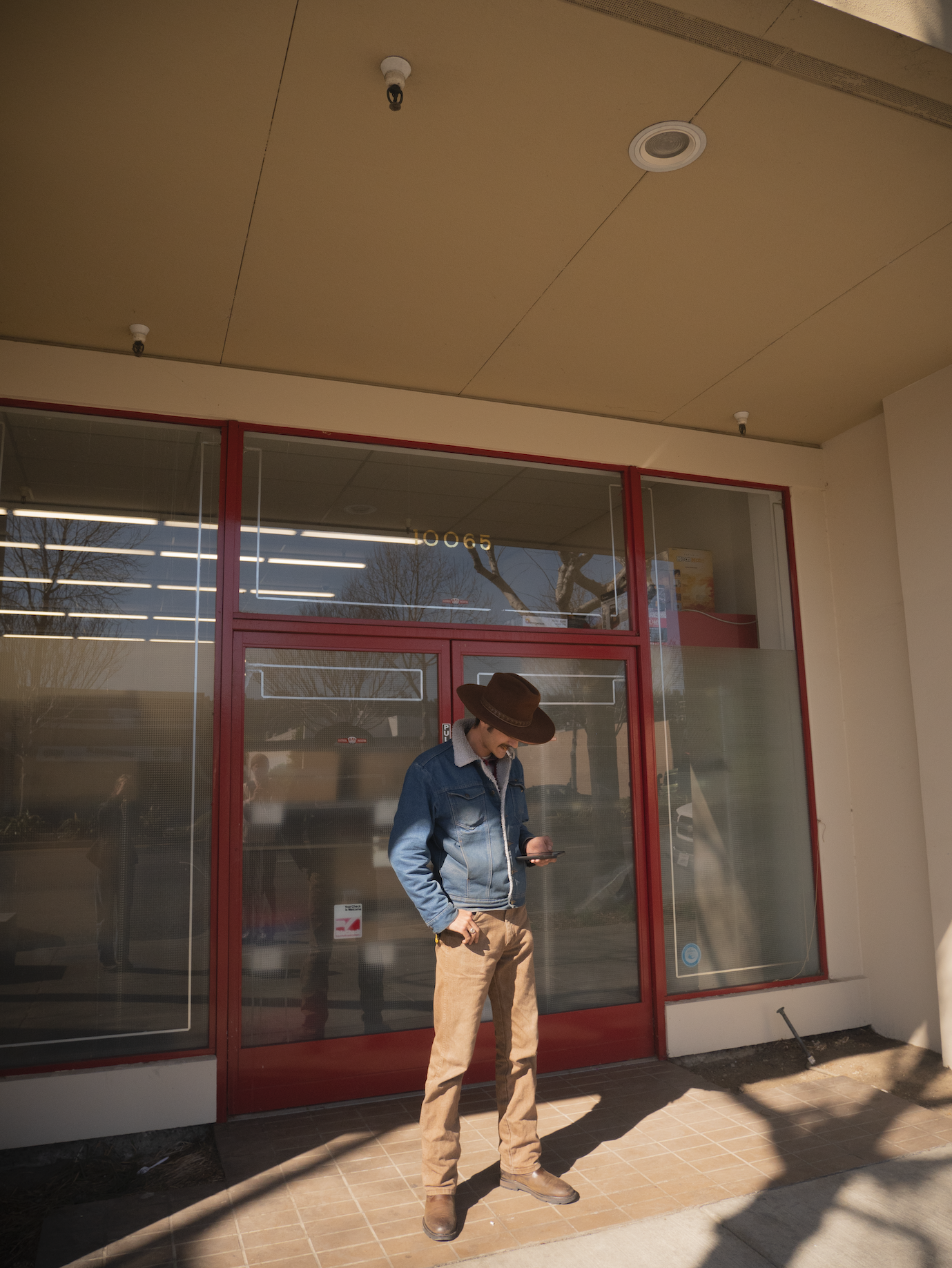

Of great importance to my understanding about each town and neighborhood we walked through, were the people we ran into on the way- many of whom which I had the privilege of speaking with briefly, and who reflected the unique geographic contexts in which they resided, worked, and inhabited. More often than not, my initial observation of San Pablo neighborhoods was a level of emptiness, or a lacking of community. However, I found through these small interactions with community members that people find community in diverse ways.

San Pablo is one of the most historically significant avenues in the bay area, having been constructed in the 1850’s with the purpose of connecting Oakland to northern East Bay cities. Here and there, I found pockets of old victorian style buildings, and other relics of the historic San Pablo, sunken into the fragmented stories of development. Beginning in Oakland - I was interested in the stark contrast between the old, empty and run-down buildings of primarily businesses and housing, against the backdrop of modern, newly renovated high rise structures. I was struck by the changing infrastructure as we moved north. Some streets seemed old industrial, others decrepit and barren, and other blocks displayed huge window-covered buildings with modern architecture. In Emeryville, we had the opportunity to speak with a few individuals, who remarked about the city’s drastic change- through covid- through neglect. As we moved into Berkeley, San Pablo became more residential, and I was welcomed by the familiar littering of discarded goodies outside of peoples’ homes. Among the old brown shingled houses with unkept yards, we spoke with a man who told us about the rich culture of protest of Berkeley’s past. In Albany, we spoke with Katarina, a Romanian woman who, after living around the world, found home in Albany’s quiet but lively streets. El Cerrito and Richmond reflected a lot of old industry: chain restaurants were interspersed wth family owned businesses. I realized that along most of San Pablo Avenue, I was able to find food from around the world, just in a few blocks. The seaside wetlands of Hercules and Rodeo offered something different. Sleepy downtown streets gave way to bustling neighborhood streets. For the first time, I saw kids playing out in the street, people waved us over and asked what we were doing- and they wanted to talk. The otherwise unremarkable small-town infrastructure was given charm through the people we spoke with. We had the privilege to listen to one man trace the history of Rodeo while sitting outside his barber shop. As the first barber shop in the area, he was proud to have stayed put despite developers not wanting a Black-owned business. As he spoke with us, probably 20 cars passed by - and he either got a friendly honk, a peace sign or wave from almost every one.

This particular experience caused me to reflect on the purpose of a city or town. Is it the relative ease and luxury of big shopping centers and centralized infrastructure - or is the natural ease of neighborhood social connection? - The people I spoke with, told their unique stories of San Pablo. I wanted to document the dignity of the people of San Pablo - amidst a changing, sometimes overwhelming, and often neglected built environment. They make San Pablo home everyday.

From the grandeur high-rises of downtown Oakland to the seaside wetlands of Hercules and Rodeo, our journey along San Pablo this semester represented a lot of the themes that I have learned about in the classroom. Drawing on political economy, we talk a lot about how people shape the spaces we inhabit- through movements of capital, gentrification, industry and transportation, methods of racialization, accumulation, and inequality. These themes were all very apparent in the shifting scenes between enormous high-rises, to unhoused communities in the underpass, strip malls and shopping complexes, to old abandoned industrial wharehouses, discarded lots, to community gardens and boutique downtowns. I felt myself most drawn to how people were making lives and communities in distinct ways within the changing landscape.

Of great importance to my understanding about each town and neighborhood we walked through, were the people we ran into on the way- many of whom which I had the privilege of speaking with briefly, and who reflected the unique geographic contexts in which they resided, worked, and inhabited. More often than not, my initial observation of San Pablo neighborhoods was a level of emptiness, or a lacking of community. However, I found through these small interactions with community members that people find community in diverse ways.

San Pablo is one of the most historically significant avenues in the bay area, having been constructed in the 1850’s with the purpose of connecting Oakland to northern East Bay cities. Here and there, I found pockets of old victorian style buildings, and other relics of the historic San Pablo, sunken into the fragmented stories of development. Beginning in Oakland - I was interested in the stark contrast between the old, empty and run-down buildings of primarily businesses and housing, against the backdrop of modern, newly renovated high rise structures. I was struck by the changing infrastructure as we moved north. Some streets seemed old industrial, others decrepit and barren, and other blocks displayed huge window-covered buildings with modern architecture. In Emeryville, we had the opportunity to speak with a few individuals, who remarked about the city’s drastic change- through covid- through neglect. As we moved into Berkeley, San Pablo became more residential, and I was welcomed by the familiar littering of discarded goodies outside of peoples’ homes. Among the old brown shingled houses with unkept yards, we spoke with a man who told us about the rich culture of protest of Berkeley’s past. In Albany, we spoke with Katarina, a Romanian woman who, after living around the world, found home in Albany’s quiet but lively streets. El Cerrito and Richmond reflected a lot of old industry: chain restaurants were interspersed wth family owned businesses. I realized that along most of San Pablo Avenue, I was able to find food from around the world, just in a few blocks. The seaside wetlands of Hercules and Rodeo offered something different. Sleepy downtown streets gave way to bustling neighborhood streets. For the first time, I saw kids playing out in the street, people waved us over and asked what we were doing- and they wanted to talk. The otherwise unremarkable small-town infrastructure was given charm through the people we spoke with. We had the privilege to listen to one man trace the history of Rodeo while sitting outside his barber shop. As the first barber shop in the area, he was proud to have stayed put despite developers not wanting a Black-owned business. As he spoke with us, probably 20 cars passed by - and he either got a friendly honk, a peace sign or wave from almost every one.

This particular experience caused me to reflect on the purpose of a city or town. Is it the relative ease and luxury of big shopping centers and centralized infrastructure - or is the natural ease of neighborhood social connection? - The people I spoke with, told their unique stories of San Pablo. I wanted to document the dignity of the people of San Pablo - amidst a changing, sometimes overwhelming, and often neglected built environment. They make San Pablo home everyday.