Absence as Presence

by Avery DavisThe city landscape is complex, often revealing misconceptions and hidden truths if one looks closely. New to the built environment of San Pablo Avenue, I set out to discover how my photographs could speak as a narrative to these urban geographies. These spaces shape the lives of thousands of people, where streets act as borders to witness microcosms of change. A stretch of land that shifts across many cultural backgrounds, my hope for this project was to create a photographic exploration of the accumulated traces of activity, and what lingers after movement, departure, and attention fade or drift elsewhere. My work strives to document these stories as such, focusing on the juxtaposition between community and the remnants of life along San Pablo Avenue. In times of transition, communities face threats to their own livelihood, being displaced or priced out of neighborhoods. This is their home; urban enclaves where they have seen generations of milestones, hardships, and celebrations. Even if not physically here, every piece of their story becomes a thread woven into the city’s collective fabric. As San Pablo faces rapid change and redevelopment, how might these images serve as a form of living memory, preserving what is disappearing even as the city transforms? Even as things appear absent or abandoned, people are still very much present. These spaces carry the weight of what is no longer there, yet hint at the human stories that persist around the edges.

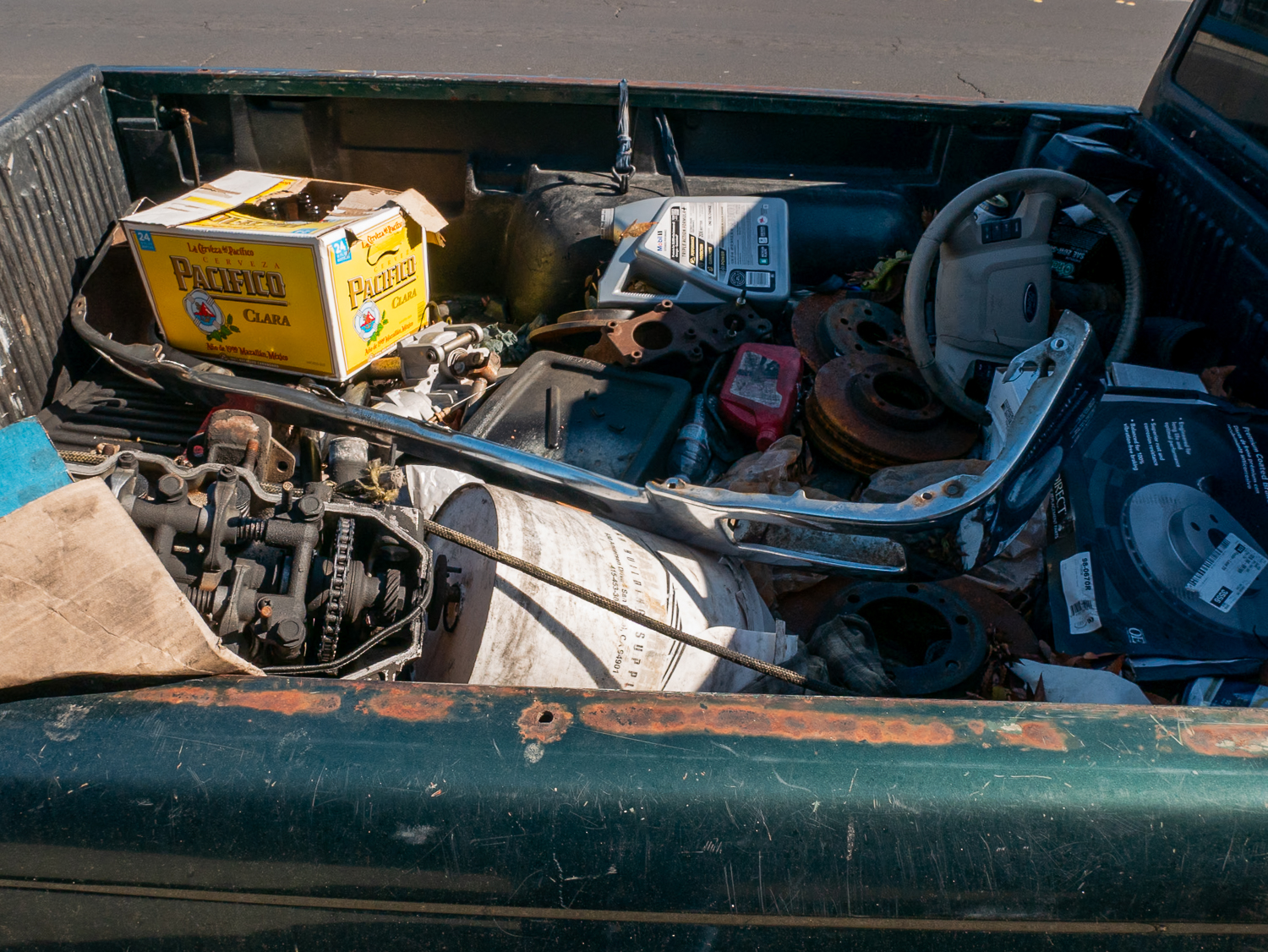

The many discoveries along San Pablo Avenue that drew my attention were not their emptiness, but their residual presence. How can absence become a quiet invitation to imagine beyond what's at face value? This contrast encourages us to look closer instead of just being passive observers. A storefront, boarded and tagged, speaks not only of closure but of the community that helped build it and begs the question of what relationships have endured since. The belongings we carry in our cars or items we leave on the sidewalk speak to what we value and cherish. By grounding this collection in images of the people we pass on our walks, I hope to capture this continuity and remind viewers that these cities remain alive—a vibrant, ongoing tapestry of experience. Things overlooked actually reveal the beauty of people and places we call home. Each person and object transcends these liminal spaces as part of our community, and we must pay attention to them. Collectively, I hope these images highlight the intimate and vivid textures of San Pablo Avenue.

I found myself drawn to the corners of the cities we explored, and photography became an essential component of understanding San Pablo Avenue. Using photography as a vessel for uplifting rather than subjugating others was of the utmost importance to me, considering the nature of photography, as in some cases, "...the camera resembles a gun, something to shoot with; in other instances, it is nothing short of extractive, a piece of equipment that takes or grabs from its surroundings. Photographers often refer to the people in front of the camera as subjects, a term that carries connotations of subjugation, of oppressive powerlessness. Even exposure—a photographic term that refers to the amount of light that reaches the camera's sensor—suggests vulnerability and risk" (Van‘t Hull).

Connecting to individuals on a human level is a small step in counteracting this history, and I found my camera bridged this gap when I approached others with honesty. I strayed away from orienting and guiding people to meet my agenda, as authenticity can not be forced. Although these conversations cannot translate through an image, I hope many of these photos "speak" for themselves. Without looking inward, I never would have met owners like Frida of Reuse for Arts & Crafts in Berkeley, (inspired by the vibrant and salient Frida Kahlo), who aspires to share her love of art and reused materials for a world that is centered around consumerism and that demands we always buy the shiniest new thing. Her ability to share the difficulties of her own experience, not only as a creative but as a business owner during the economic turmoil of COVID-19, touched me. Driving by in our cars, which are external barriers to the street, one would never know her background and what hurdles she faced to remain open and emotionally grounded in times of such uncertainty. I wanted to include these images to represent the faces behind the physical walls of the built environment. Some people did not want to be photographed along our journey; I took these as chances to listen to their stories and the legacies of shops, many of them being around for decades. Walking is a way of knowing, feeling, and experiencing our senses together at once; although I will never know San Pablo in the way of people like Frida, I carry this intimate knowledge learned from her and many others with me.

Especially over the last few years, the visual aesthetics of San Pablo Avenue have changed, with the closure of many businesses. This is present with the abundance of empty lots and for lease signs across the landscape. Now faced with propositions to expand and create new routes for transportation, building infrastructure is shifting towards this goal. The glimmers of billboard advertisements akin to "Get Money Quick" scams juxtaposed with signs of flashy new car shopping online in areas with many low-income residents point to the fact that capitalist interests are pushing aside public interests. As we walked, I saw many highlights of the bold gentrification grey and bright yellow new property development signs as we approached cities like Emeryville. However, through all of this, I noticed the signs of life in shoes perched over a balcony, graffiti, a hanging clothesline, and the like. These served as visual cues, reminding me of the tension between people and profit, and of a persistent presence that refuses to be silenced. Reviewing and collectively examining my work over the semester, all I can hope for is that I brought some justice to showing the richness of San Pablo Avenue, a living atlas, so to speak.

These photographs serve as visual footnotes to San Pablo’s complexity. Both growth and decline, and beauty and decay can exist in unison. They remind us of the hardships endured and of the absence of transition and time in our memory, even though their effects are undeniably real. It’s much easier to look away and try to fill the void than to allow ourselves to feel or grieve the loss of what once was. Community is at the center of cities, and San Pablo gives us a glimpse of how this is impacted by development and where people come and go, albeit letting their presence be known. However, we must recognize the reality of the relationship between place and space, as Doreen Massey puts it, to be this "time-space compression" that hangs over our heads in a heavily globalized world. That's exactly what this class attempts to address, as places are not static and homogeneous, but conglomerates of history, colonization, oppression, and, of course, capital relations. Boundaries have historically allowed us to neatly pick and choose what we want to care about, but to truly understand a sense of place, we must look beyond. I hope that my work carries the message to search for what might be ignored and to appreciate the rawness of everyday urban stories in a rapidly changing world.