Streets and Stories by Ellora Klein

San Pablo Avenue, a 22-23 mile-long urban stretch in the East Bay, contains a multitude of neighborhoods, communities, and ethnic enclaves, each with its own distinct character. Walking along San Pablo Avenue makes it clear how each community functions both as its own world and as a fragment of a greater whole, interconnected through the broader geography of the street. One neighborhood seems to morph into the next based on its location along the bay, its history of business and industry, and its ethnic and cultural identity. The diversity of built, natural, and cultural environments along San Pablo Avenue is what makes it so exciting, and it was interesting to see what people found most meaningful and worthy of documentation as we walked. Although everyone in our class had, for the most part, the same route, the same cameras, and interactions with the same people, we each noticed and picked up on different things, bringing our own perspectives to each interaction. One subject could have a million different ways of being perceived and portrayed, and could be found remarkable by one person and mundane by another.

As I walked down San Pablo Avenue with my camera, I often found myself wishing I could capture every sense, rather than simply vision. The sound of local business and home owners telling us stories, the taste of food from as many different cuisines as one can imagine, the smell of the flora in the wooded areas and the breads being baked in nearby bakeries, and the feeling or texture of a building or a piece of fruit being sold at a local farmers market. Initially, it felt hard to capture the diversity and vibrancy of each of San Pablo Avenue’s cities, streets, and residents in photographs, particularly because I had previously spent time on the avenue taking videos rather than images. However, as I continued to take photographs over time, I found it to be an exciting challenge to try to capture and elicit these senses through photos, so that each image held a specific feeling or story that went beyond the act of seeing, and instead into the realm of a more complete imagined sensory experience. I enjoyed thinking about photography as storytelling and worldbuilding, and viewing my images as I edited them as if through the eyes of a stranger from another part of the world. Would they too be able to imagine the sound of the laugh of the old man in Oakland’s Chinatown simply from his expression, or smell the plants at the Gill Tract farm in Albany from the look of their glowing green leaves? It was interesting to think about what information a stranger could glean from one image, and how far one’s mind could take them with just a static picture. With this in mind, I set out trying to build stories and narratives within my pictures, giving them a sense of life, motion, and feeling.

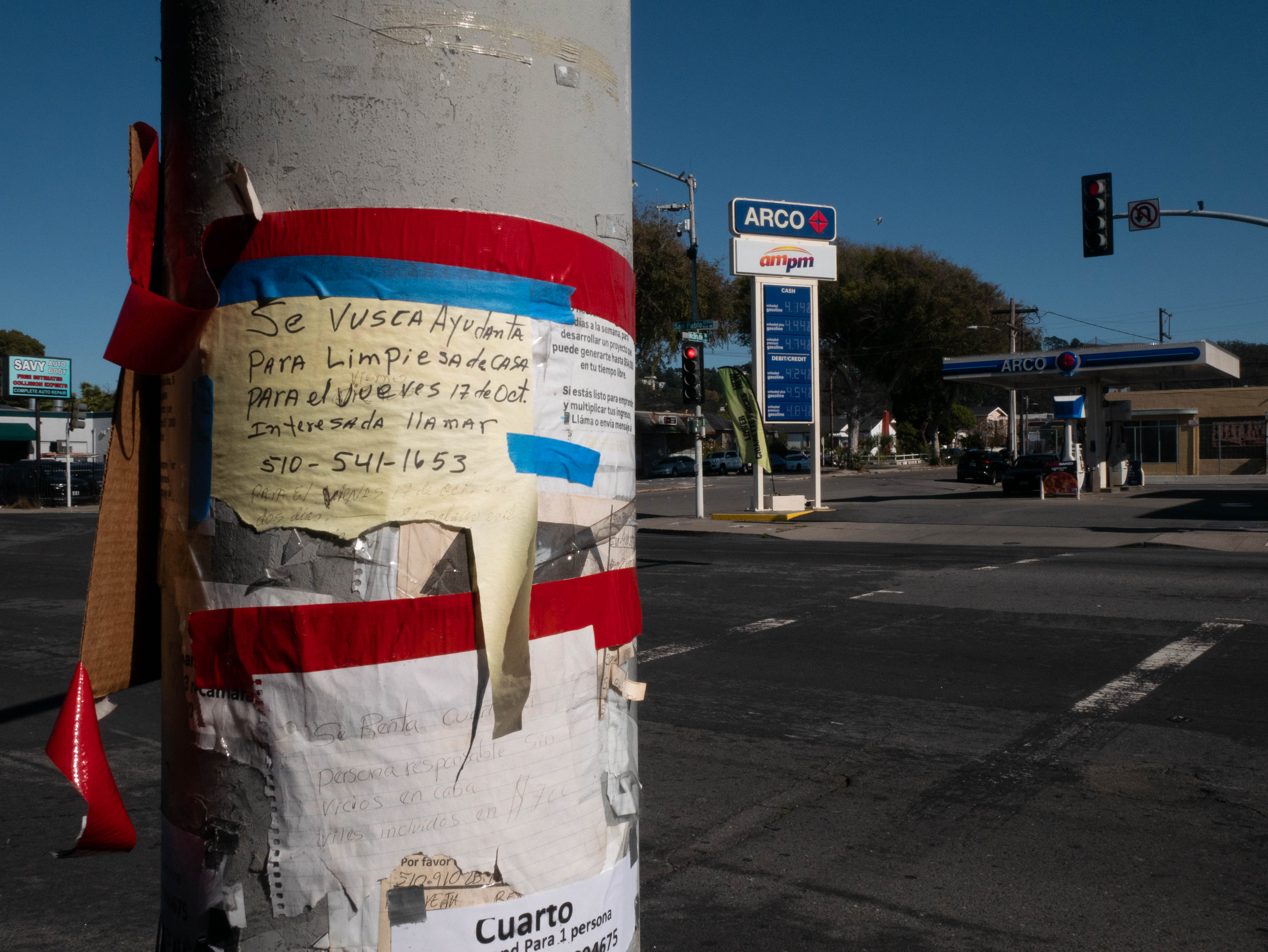

Some of the people and spaces I was met with on San Pablo Avenue made this especially easy to do, as their character seemed to shine through immediately. The local autoshops, antique stores, restaurants, markets, and all of their owners felt instantly intimate, with a character so visually obvious that it felt like a story spoke from their pictures without any need for elaborate angles or context. I found myself connected to these spaces and people, and felt an affinity towards their worlds and minds that I was allowed to enter for a fleeting moment. Many of these locals were passionate and excited to speak about their spaces, livelihoods, and neighborhoods, and telling their stories in a photo was something I enjoyed immensely. I also found myself particularly drawn to inanimate things that seemed to tell a story in a neighborhood, giving it character and bringing it to life, such as street art, found and lost objects, and interesting colors and textures. These distinguishing objects and features seemed to express and reflect the sentiments and culture of the locals even in their inanimacy, telling the story of the area they were in. They made the spaces we passed through feel like a home to someone, and I found myself photographing these features the most. Graffiti, murals, and signs were a prime example of this, as the distinct humanness of something hand drawn or written made each wall and building feel like a lived-in space that was experienced and cared for by someone. Rather than a blank wall or a lifeless billboard, a handwritten sign like those we saw on the poles of Richmond gave the neighborhood a sense of life and community that I really enjoyed exploring and connecting with.

As we discussed how each neighborhood has been changing and evolving over the years, particularly towards gentrification, it also became clear how important this kind of photographic storytelling is for preservation. It felt significant to try to depict these changes in my images, and to allow them to act as a living archive. As we passed by local fifty-year-old businesses sitting beside impersonal two-year-old condos, it became increasingly obvious how rapidly some of the neighborhoods along San Pablo Avenue are shifting, and how special it is to be able to engage with some of the older businesses that have survived thus far, but may not be able to afford their spaces in the years to come. There were also many vacant lots and abandoned buildings and houses, often donning large yellow signs depicting ambiguous development plans that may or may not come to fruition. I found these spaces to be especially interesting, as they represented to me transient domains of change that seemed to embody something significant in their emptiness. Growing up in New York City, it felt rare to encounter a space without a building, or at least some kind of park or built environment. In both NYC and Berkeley, it feels like every square foot is profited off of or put to use, and those that aren’t are constantly being contested in battles between those who want to maintain it as a free space and those who want to develop it. Thus, seeing a vacant lot or empty house to me sometimes tells an even more interesting narrative than a building. Since I’ve only lived in Berkeley for the past few years, I often don’t have any context for these empty spaces. I don’t know who once lived there, what once occupied the space, or what’s to come. Their emptiness suggests evolution, yet they also feel strangely separate from time, resisting the rapid changes and developments happening around them. Oftentimes, some form of nature seems to have reclaimed these spaces, with developers competing with cats and tall buildings competing with tall grass. They become places of possibility, where one hopes something will emerge that is beneficial to the community and contributes to its character, although the result is often an unidentifiable modern building.

We encountered people who spoke about these spaces and the changes occurring in their neighborhoods, who often echoed one another in a desire to keep these areas in the hands of locals. They didn’t want to see their homes overrun with development, but many also faced a reality of being unable to afford to keep these properties. Stories of what once existed along San Pablo Avenue faced us at every corner, and it seemed like only fragments of each block had sustained themselves over the past couple of decades. It made me think a lot about what can actually be distinguished as positive change within a neighborhood or community, and how new demographics and new buildings moving into these neighborhoods can disrupt the sense of community and home, possibly at a point rendering the area unidentifiable and stranger to those that were once locals. I also thought about how I myself play a role in this, as a student moving into Berkeley and exploring neighborhoods of the Bay Area where I can afford to dine at an expensive cafe but many of the locals can’t. These trains of thought made me reexamine my role as a photographer, but also made photography seem even more valuable to me as a way of preserving a home and telling the story of a place that may look totally different in the next couple of decades.

Engaging with, thinking about, and using photography as a means to document homes, stories, and change on San Pablo Avenue allowed me to learn a lot about what it means to enter a space that isn’t mine. As an outsider in many of the cities on San Pablo Avenue, I learned how to be mindful, careful, and compassionate in my interactions with both the built and natural environment and the people inhabiting it, and how to attempt to contribute to a community in a way that is positive and beneficial to the locals. Our ventures also changed the way I thought about art, photography, and engagement, and how it can be extractive, even without intending to be. I tend to think of art as inherently positive, but in actually entering a space as an artist, documentarian, and storyteller, I found it to be a lot more complex than I had imagined, prompting me to move with care. As someone passing through, I didn’t want my photography to operate as a one-sided venture, but rather as something collaborative, reciprocal, and joyful.

As I walked down San Pablo Avenue with my camera, I often found myself wishing I could capture every sense, rather than simply vision. The sound of local business and home owners telling us stories, the taste of food from as many different cuisines as one can imagine, the smell of the flora in the wooded areas and the breads being baked in nearby bakeries, and the feeling or texture of a building or a piece of fruit being sold at a local farmers market. Initially, it felt hard to capture the diversity and vibrancy of each of San Pablo Avenue’s cities, streets, and residents in photographs, particularly because I had previously spent time on the avenue taking videos rather than images. However, as I continued to take photographs over time, I found it to be an exciting challenge to try to capture and elicit these senses through photos, so that each image held a specific feeling or story that went beyond the act of seeing, and instead into the realm of a more complete imagined sensory experience. I enjoyed thinking about photography as storytelling and worldbuilding, and viewing my images as I edited them as if through the eyes of a stranger from another part of the world. Would they too be able to imagine the sound of the laugh of the old man in Oakland’s Chinatown simply from his expression, or smell the plants at the Gill Tract farm in Albany from the look of their glowing green leaves? It was interesting to think about what information a stranger could glean from one image, and how far one’s mind could take them with just a static picture. With this in mind, I set out trying to build stories and narratives within my pictures, giving them a sense of life, motion, and feeling.

Some of the people and spaces I was met with on San Pablo Avenue made this especially easy to do, as their character seemed to shine through immediately. The local autoshops, antique stores, restaurants, markets, and all of their owners felt instantly intimate, with a character so visually obvious that it felt like a story spoke from their pictures without any need for elaborate angles or context. I found myself connected to these spaces and people, and felt an affinity towards their worlds and minds that I was allowed to enter for a fleeting moment. Many of these locals were passionate and excited to speak about their spaces, livelihoods, and neighborhoods, and telling their stories in a photo was something I enjoyed immensely. I also found myself particularly drawn to inanimate things that seemed to tell a story in a neighborhood, giving it character and bringing it to life, such as street art, found and lost objects, and interesting colors and textures. These distinguishing objects and features seemed to express and reflect the sentiments and culture of the locals even in their inanimacy, telling the story of the area they were in. They made the spaces we passed through feel like a home to someone, and I found myself photographing these features the most. Graffiti, murals, and signs were a prime example of this, as the distinct humanness of something hand drawn or written made each wall and building feel like a lived-in space that was experienced and cared for by someone. Rather than a blank wall or a lifeless billboard, a handwritten sign like those we saw on the poles of Richmond gave the neighborhood a sense of life and community that I really enjoyed exploring and connecting with.

As we discussed how each neighborhood has been changing and evolving over the years, particularly towards gentrification, it also became clear how important this kind of photographic storytelling is for preservation. It felt significant to try to depict these changes in my images, and to allow them to act as a living archive. As we passed by local fifty-year-old businesses sitting beside impersonal two-year-old condos, it became increasingly obvious how rapidly some of the neighborhoods along San Pablo Avenue are shifting, and how special it is to be able to engage with some of the older businesses that have survived thus far, but may not be able to afford their spaces in the years to come. There were also many vacant lots and abandoned buildings and houses, often donning large yellow signs depicting ambiguous development plans that may or may not come to fruition. I found these spaces to be especially interesting, as they represented to me transient domains of change that seemed to embody something significant in their emptiness. Growing up in New York City, it felt rare to encounter a space without a building, or at least some kind of park or built environment. In both NYC and Berkeley, it feels like every square foot is profited off of or put to use, and those that aren’t are constantly being contested in battles between those who want to maintain it as a free space and those who want to develop it. Thus, seeing a vacant lot or empty house to me sometimes tells an even more interesting narrative than a building. Since I’ve only lived in Berkeley for the past few years, I often don’t have any context for these empty spaces. I don’t know who once lived there, what once occupied the space, or what’s to come. Their emptiness suggests evolution, yet they also feel strangely separate from time, resisting the rapid changes and developments happening around them. Oftentimes, some form of nature seems to have reclaimed these spaces, with developers competing with cats and tall buildings competing with tall grass. They become places of possibility, where one hopes something will emerge that is beneficial to the community and contributes to its character, although the result is often an unidentifiable modern building.

We encountered people who spoke about these spaces and the changes occurring in their neighborhoods, who often echoed one another in a desire to keep these areas in the hands of locals. They didn’t want to see their homes overrun with development, but many also faced a reality of being unable to afford to keep these properties. Stories of what once existed along San Pablo Avenue faced us at every corner, and it seemed like only fragments of each block had sustained themselves over the past couple of decades. It made me think a lot about what can actually be distinguished as positive change within a neighborhood or community, and how new demographics and new buildings moving into these neighborhoods can disrupt the sense of community and home, possibly at a point rendering the area unidentifiable and stranger to those that were once locals. I also thought about how I myself play a role in this, as a student moving into Berkeley and exploring neighborhoods of the Bay Area where I can afford to dine at an expensive cafe but many of the locals can’t. These trains of thought made me reexamine my role as a photographer, but also made photography seem even more valuable to me as a way of preserving a home and telling the story of a place that may look totally different in the next couple of decades.

Engaging with, thinking about, and using photography as a means to document homes, stories, and change on San Pablo Avenue allowed me to learn a lot about what it means to enter a space that isn’t mine. As an outsider in many of the cities on San Pablo Avenue, I learned how to be mindful, careful, and compassionate in my interactions with both the built and natural environment and the people inhabiting it, and how to attempt to contribute to a community in a way that is positive and beneficial to the locals. Our ventures also changed the way I thought about art, photography, and engagement, and how it can be extractive, even without intending to be. I tend to think of art as inherently positive, but in actually entering a space as an artist, documentarian, and storyteller, I found it to be a lot more complex than I had imagined, prompting me to move with care. As someone passing through, I didn’t want my photography to operate as a one-sided venture, but rather as something collaborative, reciprocal, and joyful.