Multidirectional Time and Space by Nicole Shkurovich

Upon walking through San Pablo Avenue with a camera, I was impressed with the way photography as a medium for storytelling helped me create a mosaic of something otherwise very linear. Through narrative and sequence, it became possible to alter the shape of a street that generally runs across one axis. Photography allows one to play with scale, time, and rhythms. Drawing from Doreen Massey’s analysis in Travelling Time, "what the simultaneity of space really consists in, then, is absolutely not a surface, a continuous material landscape, but a momentary coexistence of trajectories, a configuration of a multiplicity of histories all in the process of being made.” I have seen this perspective embodied by the photos taken on San Pablo Avenue. While most of them have been taken in landscape, horizontally framed, my tendency is to sequence photos in chronological order. But I have found that there is no linear progression. This street, and each place we stopped at, are compositions of people and how they relate to their surroundings, both visible and invisible. They are also collages of the past, present, and future.

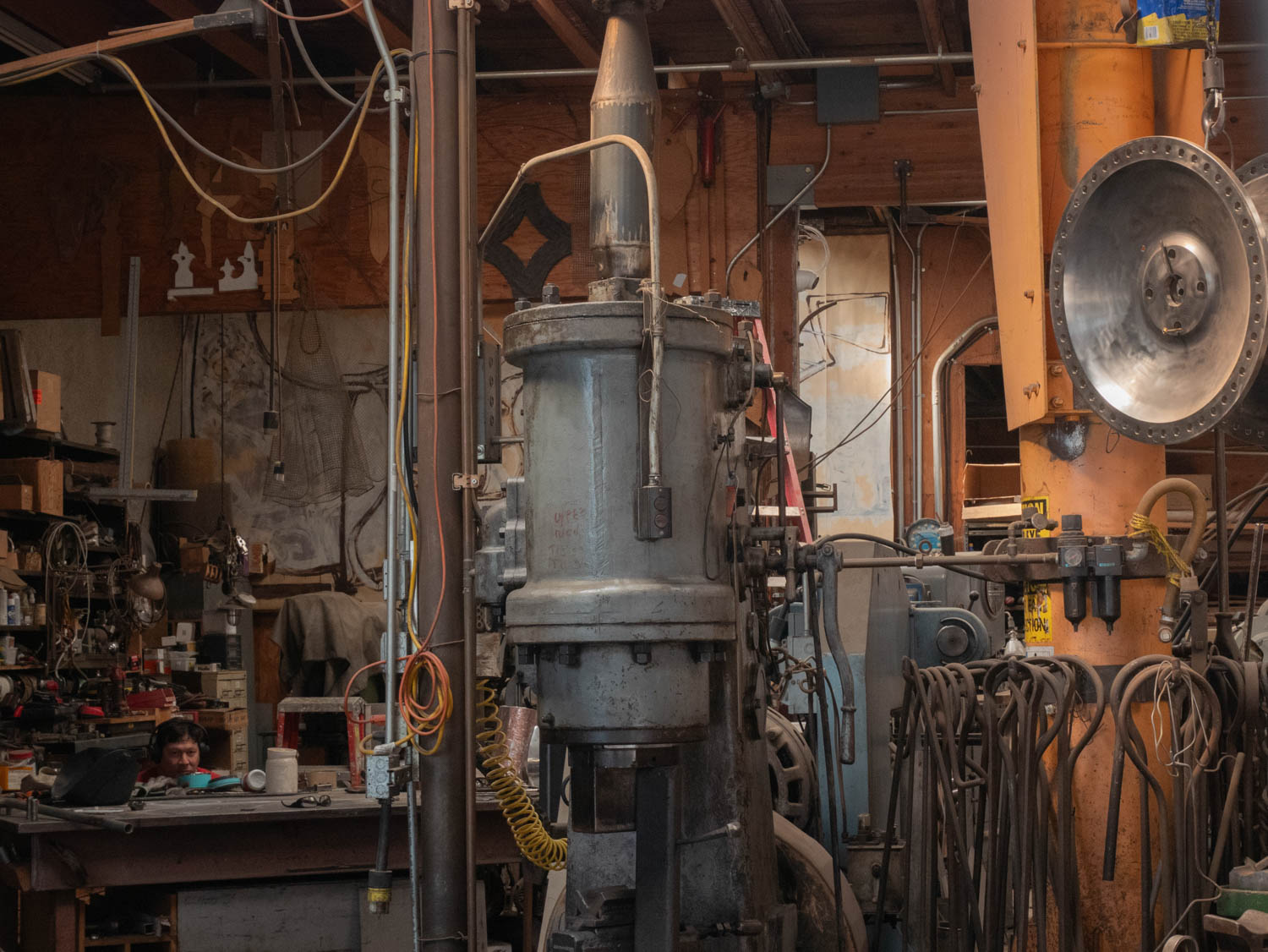

I find that there is tension ingrained in the landscape of San Pablo. The tensions exist both physically and more abstractly. The first of these tensions is between presence and absence. Who inhabits a space? How is the city’s built environment writing certain people in while erasing others? We encountered areas with legacies of racialized housing, gentrification, and intense surveillance and policing. While there is the presence of resistance—in street art and in people occupying public space— there is also a palpable absence. These absent spaces are still visible and marked; they do not simply disappear. In the in-between spaces or ones where something was left behind, one might find the histories of past communities or industries. Alternatively, one might see an absent space as potential for future development. In our city, when speculative real estate and commodification of housing is normalized, it is hard to treat these empty-seeming spaces as worthless. To me, their value is not in the future or intrinsic value, but in the social and ecological past that they represent. Maybe there is a potential for these ambiguous spaces to become something other than property.

Second, there is a tension between the local and the global. This project hones in on one specific geography. There, we might find microtrends: specialized industries, microclimates and rare ecologies, and even tight-knit social networks. First, we learned of Oakland’s history as a site of Black Panther organizing for Black liberation. Later, we encountered the history of Japanese American flower nurseries in El Cerrito. We even came to understand how the East Bay once hosted many wartime industries like explosives and shipping. And yet, with our critical lens, we can zoom out and place these images and trends into the context of the larger region, and even world. Due to colonization, and later globalization, the outside world collapses, and the fragments of it — languages, political systems, aesthetics, economies, immigration— can be picked up along the way.

Lastly, there is tension in the medium of photography itself. The photo freezes the dynamic street. The street has different rhythms. A person walking, biking, driving, taking a train. Imported goods, business transactions. We collapse the multidirectional movements of time and space into a static frame. We also attempt to engage on the interpersonal level with San Pablo, and yet, we might be limited to a relatively public sphere. We might not have always been invited to enter people’s private space, but we most certainly got to enter their personal realms. While a photo might be a snapshot, and seemingly fixed, the sequences and deconstruction of the image pull the image out of its static nature and bring the street back to life. The level of engagement with a place that we capture on our camera makes the work that we do as a class separate from photography and help form our critical geographical eye. While we may never have the definite answers about what we photograph, the camera acts as a launching point to begin interrogating and analyzing what we encounter or seek out.

While there may be tensions, there is also harmony. What photography proposes, then, is a peace with this ambivalence. The city is neither entirely inhospitable, for human and non-human, nor entirely hospitable. There is erasure, and there is resistance. Geographic photography helps one see the world through a more critical lens. It leads to an overwhelming sensation to capture every detail and quality, which may limit us from stepping back and admiring the rhythms of everyday life. When a bird lands on a crumbling roof and the colors all of a sudden find unity, or when the sun hits, painting geometric shapes onto the landscape. For me, the ultimate harmony is in taking this "simultaneous" understanding of San Pablo Avenue. The street that moves across one axis is really more multidirectional than we think: it hosts different timelines, histories, and relationships that weave into each other. We bring the past into the present through active recalling, learning, and listening. The present that we encounter, critique, converse with, and appreciate helps us also reckon and imagine the future. Photography ultimately gives way to imagine time and space in a richer way.